The week before Thanksgiving 2008 the writer stopped by an antiques shop on his way from the local public library, where he writes this GUIDE, to his apartment, a trip he makes several times a week. In a display case he was surprised to find not only a rare example of Hawkes’s remarkable Chrysanthemum pattern but also one that proved to be yet another example of the outstanding blanks used by this company during the 1890s. He first became aware of these blanks in connection with Hawkes’s Venetian pattern, an encounter he has reported on in the Venetian file. (Please see this file for additional information, including discussions of Pearson’s Relative Value Chart and the pattern-popularity poll conducted by the ACGA in 2005.) The blanks are enhanced by the excellence of the polish that is shown on these examples — mechanical polish of the highest order.

Both the Chrysanthemum and Venetian patterns (as well as their shapes) are illustrated in the c1897 [HAWKES PHOTOGRAPHIC FOLIO II] that was published by the ACGA in 2003. Close study of the items in this file, as well as the many relevant images in the c1897 catalog, suggest that they were produced during the 1890s.

Although the seller was careful to point out that the first Chrysanthemum item discussed here, a jug, has a flaw, his sales ticket mentions neither Hawkes’s nor the pattern’s name. As a consequence, the item was priced so as to constitute what antique enthusiasts often call a “find”. The writer defines this term to mean that an item has a selling price that is one-tenth or less than what an informed buyer would consider to be its “fair market value”. Not unexpectedly, the writer did not hesitate to buy the proffered jug — complete with its flaw (which is discussed later in this file)!

The Chrysanthemum pattern is often mentioned and discussed together with Hawkes’s Grecian pattern, probably because it was originally thought that both patterns were represented in Hawkes’s display in Paris at the Universal Exposition of 1889. It is now realized, however, that only the Grecian pattern, which was patented in 1887, was sent to Paris. This is not surprising given the fact that the Chrysanthemum pattern was not patented until the year after the exposition. Furthermore, when one considers Hawkes’s interest and involvement with U. S. patents, it is highly unlikely that he would have “jumped the gun” so to speak and exhibited — and on a world stage, no less — a pattern that he fully intended to eventually patent. An associated myth claims that the two patterns, Grecian and Chrysanthemum, were awarded Grand Prizes in Paris. In fact, no prizes were given for individual patterns. Hawkes was awarded the Grand Prize for the high quality of his exhibit as a whole, not for any particular pattern (Spillman 1996). But dealers find this is a strong selling point and many of them — at least those who are more interested in the bottom line than in truthfulness — continue to erroneously advertise these two patterns as “grand-prize winners.”

Both of these so-called Parisian patterns, Grecian and Chrysanthemum, have been popular with collectors over the years. Pearson rated the Grecian pattern 1-1 and the Chrysanthemum pattern 2-1 in 1978 (Pearson 1978). And in the 2005 ACGA popularity poll the Chrysanthemum pattern makes it into the “top ten” most popular patterns (while the Grecian pattern’s rating is somewhat lower down on ACGA’s list).

One of the limitations of Pearson’s Relative Value Chart — and one of which Pearson himself was aware — is the problem of time. Patterns cut during the 1890s, for example, were still being cut well after 1900. Is it reasonable to assign only one set of rarity/quality numbers to such a pattern? Probably not, yet this is usually the procedure. Only a few patterns have been singled out as showing a variation, mainly in quality, over the years. Hunt’s Royal pattern is one that comes to mind.

The brilliance of the blanks Hawkes used during the 1890s, and the superb mechnical polishing used on their cuttings, have already been noted. Equally important is the accuracy of these cuttings. The accuracy on the items illustrated in this file, as well as what one finds in the c1897 Hawkes catalog, is consistently excellent. But as cut glass became more and more popular — especially during and after the Columbian Exposition of 1893 — cutting shops experienced increased pressure to produce cut glass in quantity. As a result, quality began to suffer. This becomes especially evident when one compares examples from the 1890s to those that were produced during the later years of the American brilliant period.

Finally, one should give T. G. Hawkes full marks for the pattern’s design itself. It is not just an unusually attractive pattern, but it is also remarkable in that it translates a naturalistic subject, a plant, into an abstraction. Some designers may have had abstraction in mind when they produced their designs, but no one carried the process through to completion as effectively as did Hawkes in his Chrysanthemum pattern. One only regrets that he did not produce additional examples during his long career.

THE PATENTED PATTERN

T. G. Hawkes & Company filed its application for a design patent for the Chrysanthemum pattern on 10 Oct 1890; the patent was granted on 4 Nov 1890. Its patent’s drawing is given above while the following quotation is taken from the patent’s specification. The numbers in the text refer to the numbers on the drawing. It seems obvious that, rather than having been written by Hawkes’s patent attorneys (Knight Brothers of Washington, D.C.) — which was the usual procedure — the specification was originally drawn up by Thomas G. Hawkes, the designer, and then approved by the attorneys.

The leading features of my design consist of the large central figure having radial leaves and the flowers between the outer portions of the leaves, thus forming what I call the “chrysanthemum” design. [1] are the leaves extending radially from a common center, having cross-cut blades [2] and ovate stalks [3]. Between the leaves are flowers [4], having central rosettes [5]. Small fans [6] appear where the leaves separate. Surmounting or located at the outer ends of the leaves between the flowers are large paired fans [7].

One might easily misinterpret the multi-ribbed fans, [6], directly beneath the flowers, [4], to represent the chrysanthemums’ stems. Hawkes, however, clearly indicates that the plants’ stems, which he calls “ovate stalks” [3], are represented by what we usually refer to as “split vesicas”. Similarly, the “cross-cut” blades, [2], that decorate the plants’ leaves are what we today call “cane, with ‘clear’, or ‘uncut’, hobnails”, in other words “standard cane.”

It is worth noting that the “boxed” 8-pt hobstars that separate the pairs of fans at the outer edge of the pattern [7], are not mentioned in the patent and, therefore, might simply be considered to be “filler”. These hobstars have 8-pt hobstars with “clear” (uncut) centers on their hobnails (not, as drawn, with double Xs). In other words, this motif is what is sometimes called a “Middlesex hobstar”; it appears on all examples of Hawkes’s Chrysanthemum pattern that the writer has seen. There are multi-pointed single stars in the corners of the boxed hobstars.

The fully-formed hobstars [4] that represent the chrysanthemum flowers, have what Hawkes calls “rosettes” in their centers — what we would call Brunswick stars. The term “rosette”, however, is ambiguous. It has been used for other motifs, by Hawkes and by others. For example, Hawkes uses it to describe the single stars found in his patented Venetian pattern. And Pearson uses the term to describe a small, compact multi-pointed hobstar. Therefore, because of this ambiguity, it is best to avoid using the term.

FIRST EXAMPLE

This rare jug has a truncated (that is, slightly abbreviated) Chrysanthemum pattern, an accommodation that is often necessary when a design that is envisioned for flat ware is applied to hollow ware. The jug’s blank, no. 472, has a slightly modified barrel shape that is cut with a scalloped rim that borders a horizontal band of notched flutes. The body of the jug contains three 22-pt hobstars (“flowers”) with 16-pt Brunswick stars on their hobnails, and its base is cut with a 24-pt hobstar that also has a 16-pt Brunswick star on its hobnail. The jug has an old-style style handle (that is, one that is applied “upside down”) with a thumb rest. It is further cut with five columns of hollow diamonds that are book-ended with a pair of flutes (panel cutting). One can see a smaller version of the jug, with two “flowers,” on p. 167 of the c1897 [HAWKES PHOTOGRAPHIC FOLIO II] (ACGA, 2003).

As mentioned previously, the jug has an in-the-making flaw: A double-blind crack in the form of a slightly twisted ribbon with an overall length of about one-quarter inch, is found in an uncut area near the jug’s rim. It is believed that this occurred when the rim was cut, the result of vibrations that caused a grain of undissolved material to “implode.”

The Chrysanthemum pattern on a jug by T. G. Hawkes & Company. Blank no. 472. Very brilliant. Has a quarter-inch flaw. Also, two small chips at edge of base that are of little significance. Capacity = 2 pints. H = 6.0″ (15.2 cm), D across handle = 6.75″ (17.1 cm), weight greater than 2.5 lb (1.1 kg). Purchased for $67.50 in Corning, NY in 2008.

SECOND EXAMPLE

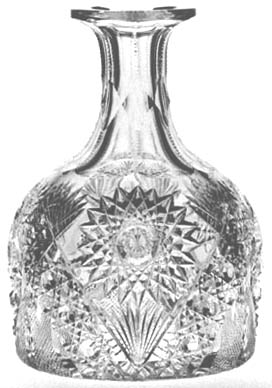

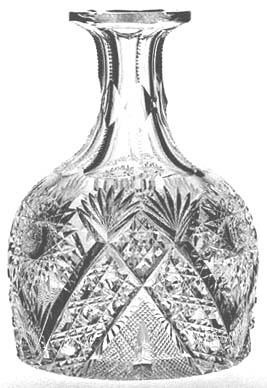

This rare example illustrates the Chrysanthemum pattern cut on hollow ware in the so-called wrap-around style. The pattern is complete; it has not been necessary to truncate it. In this example, blank no. 501 is used — a water bottle or carafe with a rounded base. This particular blank also has a neck ring, an “extra” feature that is seldom encountered, and one that is greatly appreciated by collectors.

The Chrysanthemum pattern on a water bottle or carafe by T. G. Hawkes & Company. Blank no. 501. An identical item is shown on p. 25 of the [HAWKES PHOTOGRAPHIC FOLIO II] (ACGA 2003). H = 9.25″ (23.5 cm), max D = 6.0″ (15.2 cm), wt = 5.4 lb (2.4 kg). This item was offered for sale on eBay during January 2009, but it did not sell; the bidding stopped at $300, an amount that was less than the seller’s reserve (Images: Akbarhosseini/Internet).

i. Two profile views of the Chrysanthemum water bottle:

ii. Wrap-around pattern. A view of the entire base of the water bottle that shows the convergence of the pattern as illustrated in the patent’s drawing:

ADDITIONAL EXAMPLES

A. A rare whiskey jug cut in the Chrysanthemum pattern by T. G. Hawkes & Company. Pattern truncated. Blank no. 777. 32-pt star on base. An identical item is shown on p. 46 of the c1897 [HAWKES PHOTOGRAPHIC FOLIO II] (ACGA 2003). H = 8.75″ (22.2 cm), max D = 4″ (10.2 cm), wt = 2.7 lb (1.2 kg). Offered at an eBay auction in March 2009; the highest bid, $431, failed to reach the seller’s reserve. (Images: Akbarhosseini/Internet).

Base of the whiskey jug with its 32-pt single star:

The following two examples, B and C, have been taken from the hawkes2.htm file in Part 2 of the GUIDE. The descriptions here provide some additional information:

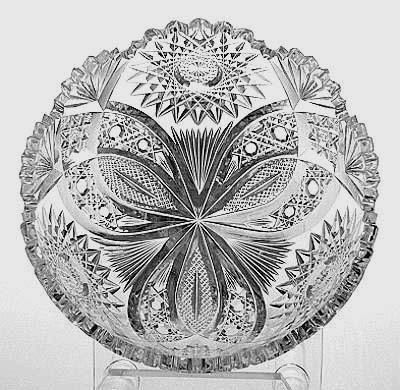

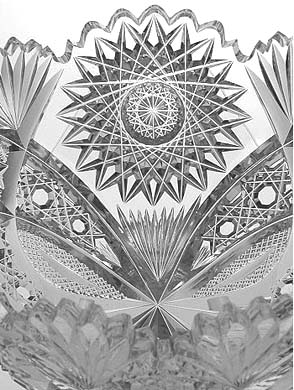

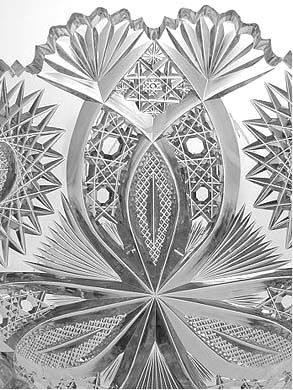

B. A scarce finger bowl cut in the Chrysanthemum pattern by T. G. Hawkes & Company. Either blank no. 350 or blank no. 385 (both with scalloped edges). D = 4.5″ (11.4 cm), H = 2.25″ (5.7 cm). Selling price unknown (Images: Internet).

Close-up views of the finger bowl:

H = 7.5″ (19.0 cm), base D = 5″ (12.7 cm), wt = 3.25 lb (1.5 lb). An identical item is found on p. 21 of the [HAWKES PHOTOGRAPHIC FOLIO II] (ACGA 2003). The

carafe sold for $300 in 1989.

Recent acquisions by the Museum are routinely announced in two publications: The Museum’s ANNUAL REPORT and an a professional publication, the JOURNAL OF GLASS STUDIES, which is also published annually. In addition, a newsletter, THE GATHER, that appears several times during the year, sometimes mentions recent acquisitions.This Chrysanthemum bowl copies the patent’s drawing exactly. It is not included in the ANNUAL REPORT for 2003, the year the bowl was acquired by the Museum, perhaps because of lack of space. It is, however, recorded in the JOURNAL, Vol. 42, p. 192, where it is accompanied by a photograph. The following is its complete entry in the JOURNAL, sans photograph:

Bowl, “Chrysanthemum” pattern, colorless, blown, cut. United States, New York, Corning. Corning Glass Works (blank) and T. G. Hawkes and Company (cutting), 1890-1900. D. 26.1 cm. The Corning Museum of Glass (99.4.78) (Image: JMH/CMoG).

The Museum also has a data base, called MIMSY. It is awkward to search and, in any case, can only be accessed by the Museum’s staff from whom page one for the item under discussion was made available to the writer. He has used it to extract the following information:

Name: A bowl with scalloped rim cut in Chrysanthemum pattern. ID number: 99.4.78. Blank made by the Corning Glass Works. Cut by T. G. Hawkes & Company. D = 10.3″ [26.1 cm], H = 3.2″ [8.2 cm]. Dates: about 1890-1900. Condition: Damaged, chipped. Source: Unknown.

Description: Colorless lead glass; blown, cut. Circular form with sides incuring slightly at serrated rim, cut into 12 scallops, four large hobstars alternate with four pointed arches formed of diamonds and hobnails, centered on a smaller arch filled with fine diamonds, all meeting in center base.

The bowl’s Description (given verbatim above) is an example of the poorly written descriptions often found in MIMSY. Note that it is incomplete. It fails to mention the design’s vesicas with miter splits — categorized by Pearson in his ENCYCLOPEDIA as “Vesica – Split”. This is a major component of the pattern and must be part of any description of it.

Most of the entries in MIMSY probably were supervised and approved by the Curator of American Glass at the Museum, Jane Shadel Spillman. Please see note 1 for those main references to Spillman’s work that were consulted during the writing of the GUIDE.